About

Background

Email was invented in the 1970’s, as a simple mechanism to send text messages from one computer to another. This was before these was even such a thing as .com or .org. Every user gave their own computer a name, and a copy of that list was shared with every user.

Fast forward over half a century to today, and email has become by far the most used 1:1 communication channel between organisations of any type. Together with the World Wide Web it holds the solid reputation of being the most widely used internet application. It was and is revolutionary, but we appreciate the convenience email offers when email service is badly disrupted.

Email does have a weak point: security was not part of its design. People were happy it worked.

Meanwhile, we conduct serious business over the internet. A lot of business. Every day hundreds of billions of emails are sent. Email is used in pretty much every industry and across our entire society, between individuals and organisations. Email is not just used to broadcast information but also used to get legally binding confirmation for business transactions. It serves as a login mechanism (“log in with your email”, “magic link”). And many millions of times every day it is used to create new accounts on services we want or need to use, or to reset lost passwords for those accounts. If someone that wants to harm you gains control over your email, there are many uncomfortable and even dangerous things they can do.

That makes email security critical for people and organisations of any type.

Email impersonation: spam and phishing

Email sent to you arrives because it is addressed to your mailserver which has a unique name on the internet. So if you are user jane@example.com, an email sent to you will be brought to the email server known as example.com. (If it were brought elsewhere, you’d have a very different problem)

One of the biggest problems with email security is that the reverse relationship does not hold. The sender of an email finds the recipient on the internet, the recipient waits for things to be delivered in their mailbox. Anyone can knock on the ports of that email server, present a message on behalf of ceo@yourfakedcustomer.example or supportdesk@you.example. People find this hard to believe, but in its original design any email can claim to be sent by anyone, and there is no telling apart real from fake.

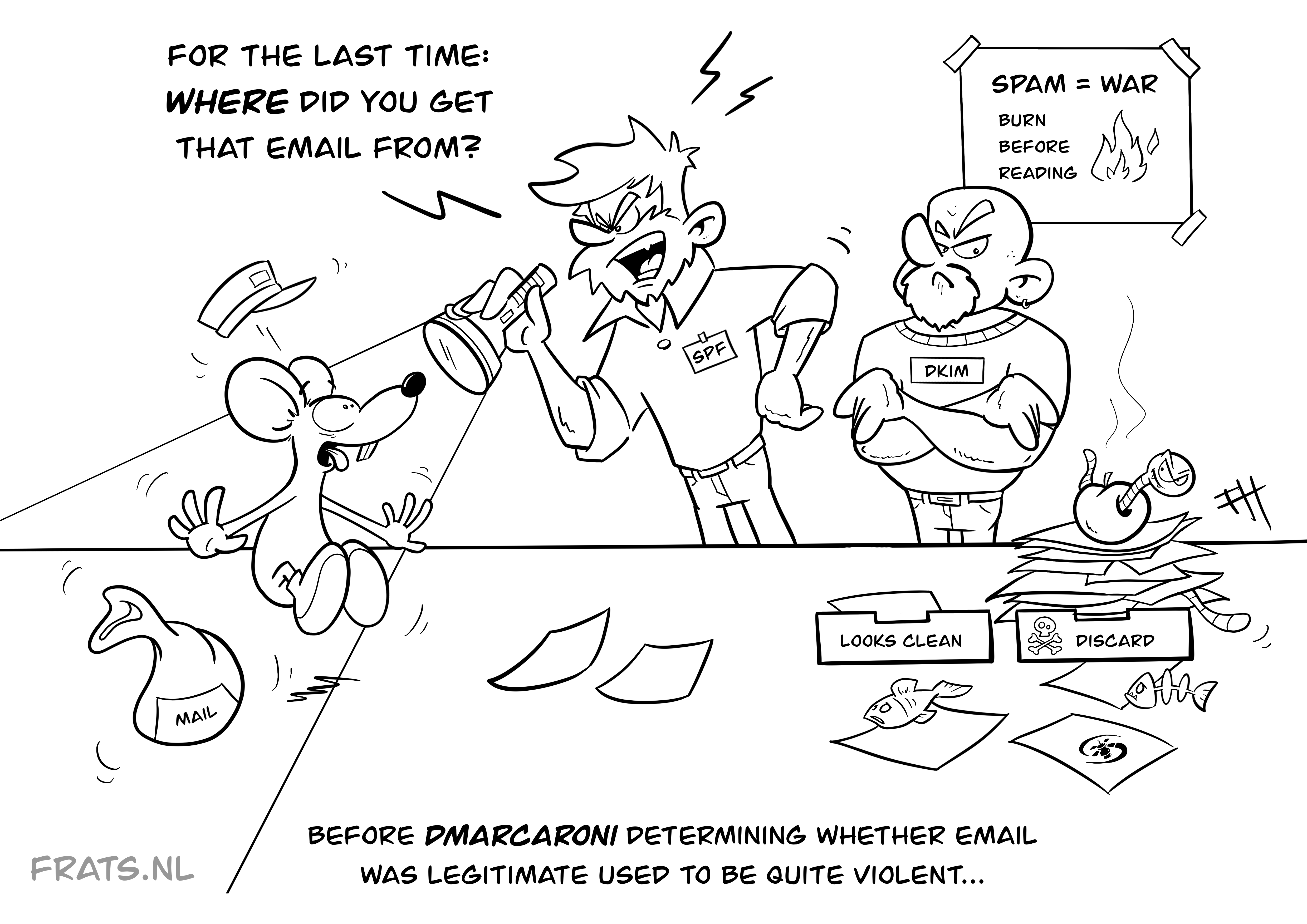

Email dates back to internal networks even older than the internet, and what an email looks like hasn’t fundamentally changed. Technically it is just the most basic of formats you can imagine: a flat text file without any markup, starting with the word “From:” followed by whatever sender address you want. Your email software may conveniently adding your “own” email address to it, but there is nothing in the original design that enforces this to be correct. As a result, the sender can just lie about it. Unfortunately, the recipient is the one that has to sort this mess out. Until SPF, DKIM and DMARC arrived there was no fail-proof way to automatically determine if an email came from a legimate sender.

Of course, this is the same for a postcard or a letter you might receive in the real world. If you get an envelope from what appears to be your bank saying that you should visit the local office to solve an urgent problem with your account, that is probably printed on an off the shelf colour laserprinter - the kind these days anyone has access to. When using the proper letterhead and using the same type of paper, they might be able to prank you to take a useless trip to the bank. If they pay a bit extra, a prankster can even have the mailman ring your doorbell and make you sign off on the fact that you’ve properly received that letter to make it more official. If they really want to hurt you, they can put explosives in a reused cardboard box from Amazon or add a toxin to a letter claiming to be from the tax office. There is no hard proof on the outside of any of those postal objects which proves the authenticity of the sender. You cannot easily judge a letter by its cover, also not in the real world.

The big difference with email on the internet is that sending fake digital messages is virtually free and without practical limits. It is possible with almost no effort and without any risk for a botherder from another side of the planet to send hundreds of millions of fake emails your way. And whether the goal of such mails is to trick you into doing something, to transport malware or to randomly advertise some weird new magical pill or adult entertainment service - it is up to the recipient fend off incoming attacks. And in the absence of any hard information, it is easy to make mistakes.

Nobody wants users to have to endlessly sift through their inbox, wading through mountains of spam and phishing emails. This is why people that run email infrastructure resort to DMARC, DKIM and SPF. These are automation-friendly instructions you give to recipients to (have their email server rather than they themselves) check emails claiming to come from you. Quick recap: DKIM adds a digital signature to email, while SPF whitelists the IP-addresses of servers that are allowed to deliver email bearing your domain name. DMARC is where everything comes together: it sets a policy on how you want all email claiming to come from you to be treated. You describe what to do in case an email fails such a check in a way that can be automated, so that the world doesn’t have to second guess. They return the favour by letting you know what they did, so that you know if you have delivery problems.

Spear-phishing and CEO fraud

Many organisations and people are quite public about who they work with: they list their customers on their website, put up notifications on social media congratulating their counterparts in other organisations with some new milestone reached, publish business cases providing detailed information on the people involved with a new implementations. Unprotected email is the ideal vehicle for social engineering.

Without SPF, DKIM and DMARC, someone can write an email purporting to be you to your customers and suppliers, using your own reputation against you. It does not take much to have people open an email from someone they trust, containing for instance malware or tricking them into making a payment or spread misinformation. If you deploy DMARC and its supporting standards and start using DMARCaroni, not only can you directly monitor any attacks towards your suppliers, but you will even prevent the vast majority of such attacks.